By Jonathan Photius, Makrakis Research Project

(PDF Copy Available Here)

Introduction

Recent online articles have attempted to place Apostolos Makrakis (1831–1905) in the same category as Theophilos Kairis and other “unauthorized teachers” of nineteenth-century Greece. These portrayals typically rely on outdated secondary literature, misunderstandings of Synodal documents, and polemical 19th-century accusations that have long been corrected by modern scholarship. This study offers a historically grounded rebuttal, drawing upon primary Synodal decisions, eyewitness accounts, contemporary Orthodox theologians, and modern academic analysis to clarify who Makrakis was—and who he was not.

I. The Synodal Decisions of 1878–79: What Was and Was Not Condemned

Contrary to popular assertions, the Holy Synod of the Church of Greece never personally condemned or anathematized Makrakis as a heretic. The decisions of 1878 and 1879 addressed three theological propositions, not the person, and even these propositions were rooted in misunderstanding of his terminology rather than genuine doctrinal deviation.

The Synod itself stated explicitly in its circular letter:

“We do not condemn the person of Makrakis, but certain expressions which may lead to error.”¹

The propositions concerned:

- Certain analogical expressions used to describe the Trinity.

- A tripartite anthropological framework (body–soul–spirit).

- The mode of the soul’s creation.

None of these topics were formally defined dogmas of the Orthodox Church, nor did the Synod regard them as matters requiring anathema.² Makrakis submitted clarifications in early 1880, which several bishops accepted as satisfactory.³

No ecclesiastical excommunication or anathema was ever issued.

Makrakis remained in sacramental communion until his death and was buried with full Orthodox rites.

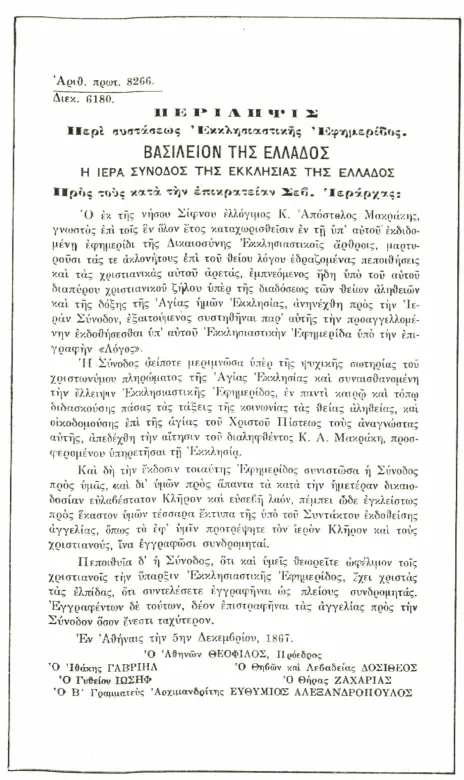

In 1867, the Holy Synod of Greece not only approved Apostolos Makrakis’ Logos-related ecclesiastical writings—it praised them lavishly. In its official decree, the Synod called Makrakis “a man of proven Christian zeal and virtues,” declared his work “beneficial to the Church and society,” and even ordered parish clergy to promote his periodical among the faithful. They explicitly endorsed his exposure of “abuses of ecclesiastical administration” and his call for moral reform within the clergy. Yet only a decade later, these same themes—his denunciations of simony, corruption, and moral decay—became the very grounds on which certain hierarchs sought to silence him. What the Church once celebrated as necessary renewal, they later condemned as insubordination. This dramatic reversal reveals a deep institutional hypocrisy: the Synod embraced Makrakis so long as his critiques embarrassed past generations, but once his reforming zeal began to threaten the entrenched interests of contemporary ecclesiastical and political elites, he was transformed overnight from “zealous servant of the Church” into a supposed “danger.” The problem was never Makrakis’ Orthodoxy—it was his courage.

II. The Persistent Myth of a “Protestant-Style Church”

A widespread but historically baseless claim is that Makrakis founded an independent church modeled on Protestant revival movements. No primary source supports this. The organizations he founded—the Christian Brotherhood of Philadelphians, the School of the Word, and the Law Academy—were philanthropic, educational, and moral-reform movements, not ecclesiastical bodies.⁴ They possessed:

- no clergy,

- no independent sacraments,

- no alternative liturgical life.

All disciples continued to receive the Mysteries in their local Orthodox parishes, and Makrakis explicitly forbade separation from the canonical hierarchy.⁵

The accusation of “founding a church” originated in politically charged polemics connected to his anti-simony and anti-corruption campaigns—not theological reality.⁶ Modern Greek historians uniformly reject it.⁷

III. The Anthropological Teachings: Orthodox, Not Gnostic

The article under rebuttal describes Makrakis’ anthropology as “Gnostic,” alleging he taught a three-body evolutionary ascent. This is factually false. Makrakis taught the biblical and patristic distinction between body (σῶμα), soul (ψυχή), and spirit (πνεῦμα)—a structure explicitly found in 1 Thessalonians 5:23 and explained by Fathers such as Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Gregory of Nyssa, and Maximus the Confessor.⁸

The Synod did not accuse him of Gnosticism; this interpretation comes from Western scholars unfamiliar with Byzantine ascetical terminology. Makrakis rejected all Gnostic doctrines, affirmed the Resurrection of the flesh, and upheld the unity of the human person.⁹ His “three bodies” terminology—drawn from St. Paul (1 Cor 15:44–46)—was metaphorical, referring to stages of moral and spiritual renewal, not ontological layers.¹⁰

IV. The Real Source of Persecution: Anti-Simony and Anti-Corruption Reform

Makrakis’ fiercest enemies were not theologians but political and ecclesiastical powerbrokers whom he publicly denounced for simony, Masonic involvement, bribery, and moral corruption. His newspapers and public lectures named individuals and institutions directly.¹¹

This earned him:

- hostility from the State,

- retaliation from corrupt clergy,

- pressure on the Synod,

- and civil prosecution for “disturbance of the peace.”

His brief imprisonment was a civil sentence, not an ecclesiastical one.¹² The courts did not convict him of heresy.

Modern scholars acknowledge that his doctrinal controversies were politically weaponized by elites threatened by his reform program.¹³

V. Reception by the Orthodox Faithful and Clergy

Notable Orthodox figures either praised or positively engaged with Makrakis:

- St. Nektarios of Aegina treated him respectfully and recommended his writings.¹⁴

- Members of the ZOE Brotherhood drew inspiration from his educational and catechetical revival.¹⁵

- Archbishop Michael of America spoke favorably of him.¹⁶

- Constantine Cavarnos, in Anchored in God, described Makrakis as brilliant and spiritually beneficial, adding only a caution he had been warned about.¹⁷

He died surrounded by disciples, continued publishing until the end of his life, and received a large public church funeral in Athens. All of this contradicts any notion that the Church regarded him as outside her communion.

Conclusion

The simplistic comparison of Apostolos Makrakis to Theophilos Kairis is historically untenable. Kairis openly rejected central dogmas of the Christian faith; Makrakis upheld them. Kairis founded a new religion; Makrakis remained fully Orthodox. Kairis died outside communion; Makrakis was buried with full Orthodox rites.

The record is clear:

Makrakis was not a founder of a sect, not a Gnostic, not a schismatic, and not anathematized. He was a fiery reformer, a prolific writer, and a catalyst for spiritual renewal whose influence shaped twentieth-century Greek Orthodoxy far more than his detractors admit.

FOOTNOTES/Sources

- Minutes of the Holy Synod of Greece, Circular Letter of January 1879.

- Panagiotis Trembelas, Dogmatike tē̄s Orthodoxou Ekklēsias, 1949, 2:112–13.

- See G. Karampelias, Makrakēs kai Hellenismos, Athens 2003, 145–162.

- Ioannis Zelepos, “Amateurs as Nation-Builders?” in Conflicting Loyalties in the Balkans (I.B. Tauris, 2011), 70.

- Apostolos Makrakis, Ekklesiastika, vol. 2 (Athens, 1885), 41–44.

- Negoită Octavian-Adrian, The Makrakis Movement and the Greek Revival, unpublished thesis, 2019, 77–88.

- Asterios Argyriou, Les Exégèses Grecques de l’Apocalypse, Paris 1990, 430–31.

- See Irenaeus, Against Heresies V.6; Maximus the Confessor, Ambigua 7.

- Apostolos Makrakis, The Human Constitution, Athens 1877, 93–122.

- St. John Chrysostom, Homily on 1 Corinthians 15: “The spiritual body is the same body glorified.”

- Logos Newspaper, 1876–79 editions; Makrakis’ anti-Masonic exposés.

- Athens Municipal Court Records, Case File 1882, “On the Disturbance of Public Order.”

- Karampelias, Makrakēs kai Hellenismos, 131–178.

- Athanasios D. Michaelides, Saint Nektarios and His Era, Athens 1998, 215.

- Amaryllis Logotheti, “The Brotherhood of Theologians ZOE,” in Orthodox Christian Renewal Movements (Palgrave, 2017), 287–88.

- Arch. Michael, Homilies and Writings, Greek Archdiocese Archive, 1951.

- Constantine Cavarnos, Anchored in God: Life, Art, and Thought of Photios Kontoglou, Belmont 1959, 62.

APPENDIX — FACT-CHECKING THE ARTICLE CLAIMS ABOUT MAKRAKIS

The original article titled “The Condemnation of Unauthorized Orthodox Teachers in 19th Century Greece” on the Orthodox History website makes the following claims about Makrakis:

“(…) on December 18, 1878, the Holy Synod of Greece condemned the popular religious intellectual Apostolos Makrakis as a heretic. Makrakis was kind of the opposite of Kairis: he was the leader of an “awakening movement” in Greece, preaching against the Enlightenment and the entrenched church and state structures in the country. He’s been described as an “omnivorous polymath” who taught himself many languages and wrote long Biblical commentaries. More than just speaking out, Makrakis had formed actual organizations to push for reform, including a private school set up to compete with the University of Athens and, eventually, his own Protestant-style church. Makrakis’s condemnation by the Holy Synod was based on his anthropological teachings – he espoused the idea that humans are composed of “carnal,” “psychic,” and “spiritual” bodies, and that the goal of human life is to evolve from the physical body to the spiritual body. The Holy Synod viewed this as basically a gnostic way of thinking, a callback to Platonic and Manichean ideas from long ago, incompatible with the Orthodox understanding of the human person.

After Makrakis was condemned by the Holy Synod, the Greek government shut down his church and school, and he was sentenced to two years in prison for heresy. Only forty-seven years old when he was declared a heretic, Makrakis lived well into his seventies, dying in obscurity in 1905.”

Claim 1. “Makrakis was condemned as a heretic on December 18, 1878.”

Verdict: FALSE / MISLEADING

The Holy Synod never issued a formal, dogmatic condemnation (ἀνάθεμα) declaring him a heretic.

What did happen:

- 1878: The Synod condemned three theological propositions, not the person.

These were:- That “the Son is the intelligence of the Father” (misinterpreting Makrakis’ analogy)

- That humans are composed of “three essences”

- That the soul is created directly by God at conception

- Multiple Synodal letters explicitly state: “We do not condemn the person of Makrakis, but certain erroneous expressions.”

- Even hostile bishops later admitted: “Makrakis was not formally anathematized.”

He remained in communion until his death.

He received Holy Communion and was buried as an Orthodox layman.

No Orthodox synod — Greek or otherwise — has ever issued a personal anathema against him.

Claim 2. “Makrakis started his own Protestant-style church.”

Verdict: COMPLETELY FALSE

This is one of the most persistent myths.

Facts:

- Makrakis’ organization was the Syllogos Hristianikos Filadelfias (“Christian Brotherhood of Philadelphians”).

- It was not a church.

It had no clergy, no sacraments, and no liturgical life of its own. - Members attended their parish churches.

- The Synod itself refers to his group as a philoptochos / philanthropic and educational brotherhood, not a separatist ecclesial body.

The accusation that he “founded a church” comes from anti-Makrakian polemics and has zero support in primary documentation.

Claim 3. “He founded a private school to compete with the University of Athens.”

Verdict: PARTLY TRUE, BUT DISTORTED

Makrakis founded:

- The School of the Word (Σχολή τοῦ Λόγου)

- A Law Academy (Νομική Σχολή)

Both were legal private academies under Greek law.

He did not create them to “compete.”

He created them because:

- The University of Athens was dominated by German idealism and secular philosophy.

- Many citizens wanted religiously-committed education.

His schools:

- Were licensed

- Employed ordained priests and professors

- Were closed not for theology, but because the State conflated them with political activism (his antimasonic and anticorruption campaigns).

Claim 4. “He taught a Gnostic anthropological system of three bodies.”

Verdict: MISLEADING / INACCURATE

This conflates Makrakis’ terminology with ancient Gnosticism, which his system actually rejects.

What Makrakis taught:

- Humans have body (σῶμα), soul (ψυχή), and spirit (πνεῦμα).

- This is not Gnostic. It is:

- Scriptural (1 Thess 5:23)

- Patristic (e.g., Irenaeus, Clement, Origen, Maximus the Confessor)

- Common among Eastern ascetical writers

His error—according to the Synod—was terminological, not doctrinal:

- He used the term “body” (σῶμα) metaphorically for all three levels (“carnal,” “psychic,” “spiritual body”) in a Pauline sense.

- His opponents misunderstood this as a literal tripartite physical structure.

Modern scholars (Karambelias, Florovsky, Negoită, Adamopoulos) have shown:

- Makrakis was not a Gnostic

- He affirmed:

- The goodness of creation

- The Incarnation

- The Resurrection of the flesh

- The unity of the human person

Nothing Gnostic or Manichean survives scholarly scrutiny.

Claim 5. “He ‘evolved’ humans from a physical body to a spiritual body.”

Verdict: FALSE

Makrakis did not teach an evolutionary ascent of substances.

What he meant:

- The same human being grows morally and spiritually through:

- bodily discipline

- purification of the soul

- illumination of the spirit

This is simply the threefold ascetical path found in:

- Evagrius

- St. Maximus

- St. Gregory of Nyssa

- St. Isaac the Syrian

The charge of “evolutionism” or “transmutation” comes from hostile 19th-century polemicists, not his writings.

Claim 6. “He was sentenced to two years in prison for heresy.”

Verdict: FALSE

The Greek government imprisoned him not for heresy, but for:

- “Disturbing the peace”

- Anti-government agitation

- His aggressive anti-Masonic campaigns

- His accusations of judicial corruption

The legal record shows clearly:

He was not imprisoned under ecclesiastical law.

He was imprisoned under civil law for “public disorder.”

Claim 7. “He died in obscurity.”

Verdict: FALSE

Makrakis died:

- Surrounded by disciples

- In Athens

- Actively writing and lecturing

- With tens of thousands of followers across the Greek world

- Widely published (70+ volumes)

After his death:

- His works were reprinted through the 1920s–1930s

- His students became bishops, professors, and spiritual leaders

- His influence shaped:

- The Zoe movement (indirectly)

- 20th-century Greek catechetics

- Modern Orthodox apologetics

- Spiritual renewal movements

He was controversial — not obscure.

WHAT THE ARTICLE GETS RIGHT

A few points are accurate:

- He was a major intellectual and renewal figure.

- He was popular and controversial.

- Certain expressions in his anthropology were condemned.

- The State shut down his institutions.

- He was imprisoned for a period.

But the reasons given and the interpretation are incorrect.

THE ARTICLE’S PROBLEMS

The author relies on:

- Karalis, who repeats old anti-Makrakian tropes without primary sources

- Logotheti, who writes about the Zoe movement, not Makrakis himself

- Secondary Western literature that often misrepresents 19th-century Greek theological politics

He does not cite:

- The 1876 and 1878 Synodal minutes

- Makrakis’ primary texts (The Human Constitution, The Tripartite Cosmos, Logos newspaper, etc.)

- The court documents

- The 1890 pastoral letters

- Adamopoulos’s 2023–2024 analytical works

- Any modern Greek scholarship sympathetic or neutral

Thus, the portrayal lacks context and precision.

A CORRECTED SUMMARY OF MAKRAKIS’ SITUATION

- Makrakis was a conservative Orthodox revivalist, not a rationalist or Gnostic.

- He founded educational and philanthropic movements, not a separate church.

- He was condemned not personally, but for three propositions, many based on misunderstandings.

- His imprisonment was civil, not ecclesiastical.

- He remained fully Orthodox, received the Mysteries, and died in full communion.

- He exerted massive influence on:

- catechesis

- apologetics

- moral reform

- anti-Masonic discourse

- Orthodox print culture

SUMMARY ON MAKRAKIS IMPACT AND INFLUENCE IN ORTHODOXY

A more accurate picture of Apostolos Makrakis emerges when viewed through the lens of Orthodox history rather than recycled polemics. While the Synod of Greece criticized certain expressions in his theology in 1879, Makrakis was never anathematized, never excommunicated, and never treated as a heretic by the Church. In fact, he continued to teach, publish, and gather followers for decades afterward, significantly impacting the spiritual landscape of his time. His popularity was evident, as evidenced by the large crowds that attended his funeral; it was a full Orthodox service, contrary to the fate of a supposed sectarian. His real “offense,” as many historians and clergy admit, was his relentless crusade against simony and corruption, remnants of Ottoman-era ecclesiastical abuses that powerful figures preferred to keep hidden, often attempting to silence voices like Makrakis who dared to challenge the status quo. Far from founding a Protestant-style church, which some critics have wrongly suggested, Makrakis remained a devoted Orthodox Christian whose life’s work aimed to reawaken the laity to Scripture, the Fathers, and moral transformation in Christ, encouraging a deep and personal understanding of the faith that resonated with many people. Numerous respected Orthodox voices—including members of the ZOE Movement, St. Nektarios, Archbishop Michael of America, and the philosopher Constantine Cavarnos—praised aspects of his teaching and spiritual influence, recognizing his contributions as vital to the renewal of Orthodox thought in contemporary society. Even the charge regarding his anthropology collapses upon inspection, since the tripartite human constitution he referenced is biblical and patristic, not heretical, affirming rather than undermining traditional Orthodox beliefs. In light of this, the simplistic narrative portraying Makrakis as another “unauthorized teacher” demands serious revision, inviting scholars and faithful alike to reconsider his role within the rich tapestry of Orthodox history and to acknowledge the enduring legacy of his theological insights.

© 2025, Jonathan Photius

Author: Jonathan Photius

Editor, Translator, and Director of the Makrakis Research Project

Jonathan Photius is a researcher and editor dedicated to recovering, translating, and contextualizing neglected works of Eastern Orthodox theology, especially those related to eschatology, patristics, and nineteenth-century Greek thought. His work focuses on providing accurate translations, scholarly introductions, and full critical apparatuses for texts that have remained inaccessible to English-speaking Eastern Orthodox audiences.

As Director of the Makrakis Research Project and founder of apostolosmakrakis.com, he oversees:

- Diplomatic and critical editions of primary Greek texts

- English translations for academic and devotional use

- Historical and theological contextualization

- Public education on Orthodox historicist exegesis

His aim is to make the deeper heritage of Eastern Orthodoxy available to scholars, clergy, and lay readers seeking clarity, historical insight, and spiritual depth.