Apostolos Makrakis: Life, Formation, and Legacy – A Study Based on the 1957 Commemorative Essay by Theodoros Sperantzas

Introduction

The commemorative study Ὁ Ἀπόστολος Μακράκης, published in Athens in 1957 on the fiftieth anniversary of Apostolos Makrakis’ death, occupies a distinctive place in modern Makrakis scholarship.¹ Written by Theodoros Sperantzas, former Royal Commissioner to the Holy Synod, Grand Logothete of the Church of Greece, and director of the official ecclesiastical periodical Ἡ Ἐκκλησία, the work represents not a partisan defense but an institutional reassessment by a senior church official.² Its value lies not only in its conclusions but in the biographical detail it preserves—especially regarding Makrakis’ early life, formation, and educational activity, areas often neglected or distorted in later polemical accounts.

This article highlights and summaries the contents of Sperantzas’s 31-page booklet which I have translated from Greek to English.

by Theodoros Sperantzas

Reprint from the commemorative album on the fiftieth anniversary since his death

Athens, 1957

Birthplace, Family, and Early Environment

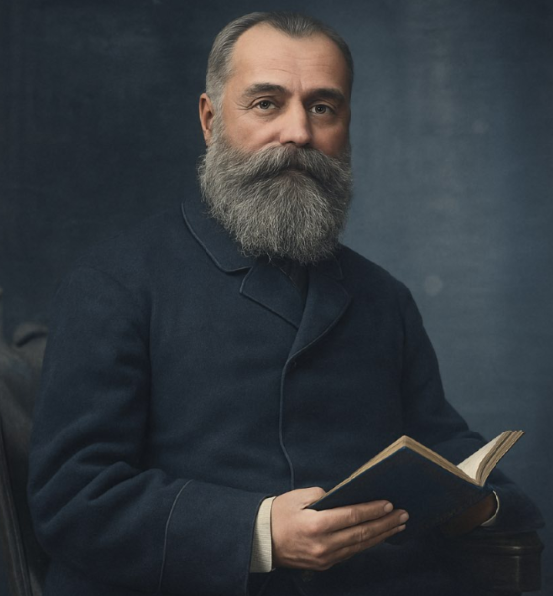

Sperantzas situates Apostolos Makrakis firmly within his island origins. Born on Siphnos, one of the Cyclades, Makrakis is presented as a product of a moral environment shaped by simplicity, austerity, and Orthodox piety.³ Siphnos functions in the narrative not merely as a place of birth but as a formative spiritual landscape, implicitly contrasted with the moral and social decay Makrakis would later denounce in urban Greek society.

One of the most significant early biographical details preserved by Sperantzas is that Makrakis was raised by a very pious mother.

“That which, however, exercised the greatest influence upon the formation of his inner life, and more generally upon the shaping of his character and of his interior impulses and dispositions, was his most pious mother. Blessed be her memory! Her name was Aikaterini, and she was of the family of Koulouri, and by common admission she possessed gentleness, endurance, sweetness, love of work, and an exceptional philanthropy and tenderness of affection. She was moreover adorned with great piety and a fervent faith. And as I heard during my childhood from the most reverent presiding priest of Vrysi and then parish priest of Katavati, Avekios Gerontopoulos, she took the lead in seeing that the books and vessels were returned to the sacred Monastery of Saint John the Theologian (Mougou), which after its violent dissolution by the Bavarians had been scattered among the surrounding inhabitants.“⁴

The maternal household clearly emerges as the crucible of Makrakis’ moral seriousness and emotional intensity, marked by sacrifice and inward discipline rather than privilege or institutional patronage.

Early Education and Awakening of Vocation

Makrakis’ early education combined classical learning with religious and moral instruction.⁵ From an early age he exhibited seriousness of temperament and intellectual intensity. Sperantzas emphasizes that Makrakis’ later trajectory was not the result of sudden inspiration or ideological accident, but the organic development of traits already present in youth: a restless concern for truth, intolerance of hypocrisy, and a conviction that knowledge imposed ethical responsibility.⁶

Education, for Makrakis, was never neutral. It was always oriented toward the transformation of the person, which explains why Sperantzas presents him initially not as a polemicist but as a teacher and moral educator.⁷

The Educator Before the Controversialist

Before his emergence as a public preacher, Makrakis devoted himself to teaching philology, philosophy, religious instruction, and ethics.⁸ His pedagogy aimed not merely at instruction but at formation of conscience, requiring students to engage directly with Scripture and integrate Christian teaching into daily life.⁹

Already at this early stage, Makrakis encouraged frequent participation in Holy Communion, provided it was accompanied by repentance and spiritual preparation.¹⁰ Sperantzas presents this practice as sincere pastoral zeal, while acknowledging that it provoked suspicion—foreshadowing the conflicts to come.¹¹

From Classroom to Nation

A decisive turning point occurred when Makrakis concluded that educating a limited circle of students was insufficient to address what he perceived as a profound moral and spiritual crisis afflicting Greek society.¹² From this point forward, he redirected his energies toward public preaching, lecturing, and writing as instruments of national and ecclesial awakening.¹³

Makrakis’ preaching in Athens drew large crowds and strong reactions. Sperantzas insists that its severity flowed from love of truth rather than personal animosity, noting that Makrakis “adored the truth. And he adored it with passion… and with open eyes… without ever closing them before any form of shame, nor compromising with falsehood and ignorance.”¹⁴

Tone, Polemic, and the Sword of Truth

Sperantzas offers a sustained defense of Makrakis’ rhetorical intensity. He acknowledges that Makrakis could be forceful and uncompromising, yet denies that this constituted hypocrisy or bad faith.¹⁵ Instead, Makrakis is likened to a prophetic figure whose speech bore the violence of moral urgency rather than personal rage. His preaching, Sperantzas observes, often assumed “the violence of a storm, of hail, and of blazing fire.”¹⁶

This imagery is grounded explicitly in biblical precedent. Drawing on Sinai typology, Sperantzas asks rhetorically: “Since when is the fire by which weeds are burned away considered the fire of insane punishment?”¹⁷

Conflict with Authority and the Limits of Method

Sperantzas does not conceal Makrakis’ conflicts with ecclesiastical authority. He concedes that Makrakis’ rigidity became “his Achilles’ heel, which successfully fueled the persecutions of his opponents.”¹⁸ Yet this admission is immediately balanced by a firm assertion of Makrakis’ sincerity and Orthodoxy.

Despite all conflicts, Sperantzas insists unequivocally that Makrakis “remained a faithful child of the Orthodox Church.”¹⁹ Whatever Makrakis spoke or wrote, “he believed unshakably as truth, which he had received from God the command to proclaim.”²⁰ His failures, if such they were, lay in method and temperament, not in intention or faith.

Trials, Suffering, and Perseverance

Makrakis’ trials, condemnation, and imprisonment are presented not as evidence of fanaticism but as episodes of suffering that clarified his sense of mission.²¹ Persecution did not silence him; rather, it intensified his commitment to teaching and writing.²² Even in marginalization, he remained disciplined, productive, and convinced of his divine calling.²³

Death and Posthumous Reassessment

Makrakis’ death in December 1905 is described with reverence. In his final hours, he entrusted himself fully to God, praying: “My God, if I no longer have work here, take me… and give me rest near You, if this is Your holy will.”²⁴

Looking back after fifty years, Sperantzas concludes that time itself clarified Makrakis’ legacy: “Now that the wave of time which has flowed by has cleansed his spiritual physiognomy, absolutely no one can dispute that he was pure in intention and most Christian in disposition.”²⁵ Even in the present, he adds, Makrakis’ works “continue to teach, console, move to compunction, renew, and become a spiritual bridge that truly carries one from Earth to Heaven.”²⁶

Conclusion

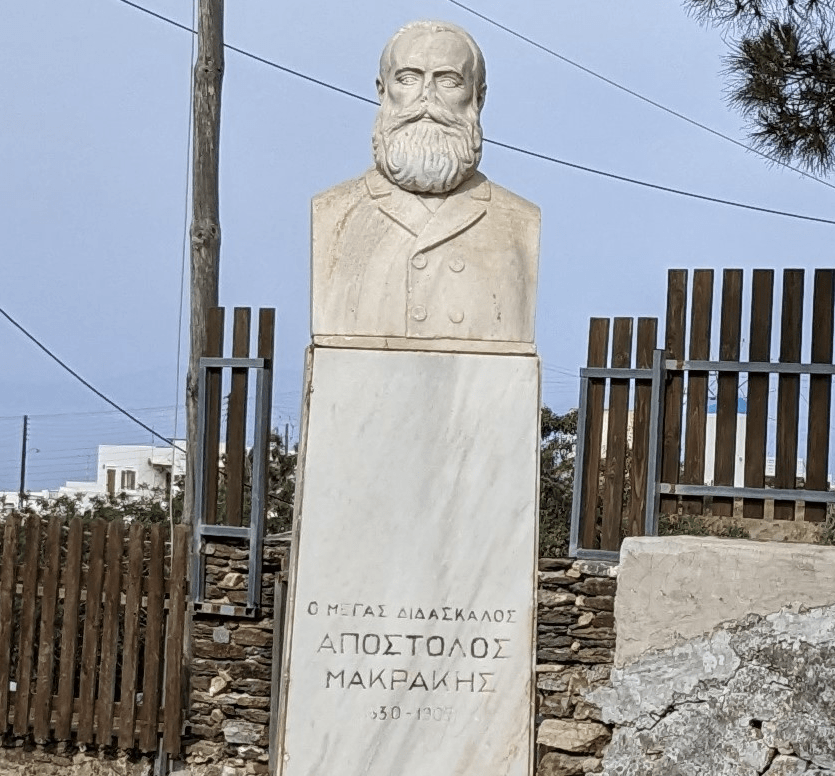

The study concludes not with monument-building but with prayer. Sperantzas explicitly rejects the erection of statues and instead appeals to ecclesial memory, forgiveness, and sanctification.²⁷ He closes by asking that the Church manifest toward Makrakis “her magnanimous and great-souled forgiveness and love, and through her prayers and blessings sanctify his holy memory.”²⁸

Footnotes

- Theodoros Sperantzas, Ὁ Ἀπόστολος Μακράκης (Athens: 1957), title page.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 27–28.

- Ibid., 27.

- Ibid., 26–27.

- Ibid., 27–28.

- Ibid., 26.

- Ibid., 26–27.

- Ibid., 26.

- Ibid., 26–27.

- Ibid., 27.

- Ibid., 27–28.

- Ibid., 27–28.

- Ibid., 28.

- Ibid., 28–29.

- Ibid., 28.

- Ibid., 29.

- Ibid., 28.

- Ibid., 31.

- Ibid., 31.

- Ibid., 29–30.

- Ibid., 30.

- Ibid., 30.

- Ibid., 27.

- Ibid., 28.

- Ibid., 31.

- Ibid., 31.

- Ibid., 31.

Bibliography

Sperantzas, Theodoros. Ὁ Ἀπόστολος Μακράκης: Ἀνάτυπον ἐκ τοῦ ἀναμνηστικοῦ λευκώματος ἐπὶ τῇ πεντηκονταετηρίᾳ ἀπὸ τοῦ θανάτου αὐτοῦ. Athens, 1957.

The best book you can read about Makrakis history is ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ ΤΟΥ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΔΙΔΑΣΚΑΛΟΥ ΑΠΟΣΤΟΛΟΥ ΜΑΚΡΑΚΗ by ΜΗΝΑΣ ΧΑΡΙΤΟΣ. I have translated to modern Greek almost most of Makraki’s books. I hope and pray someone will be interested to take them and make them available to the Greek people, here in Greece. I live here, near Ancient Corinth. I’ve even have found many of his original books, published in the 1800’s

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Andreas,

I do have a copy of that one as well I ordered from a bookshop in Greece and had it shipped to the United States! It is 832 pages and I will start to translate it into English, but it will be an enormous task! I ordered a few Greek biographies from Makrakis and have started translating the shorter works first into English. My plan is to publish a modern English biography on his life and works, as well as translate some of his earlier works into English that were not republished by the Orthodox Christian Education Society back in the mid 1900s. God willing! +++

LikeLike